Friday, 6.22am

Toronto, Canada

Let’s say intelligence is your ability to compose poetry, symphonies, do art, math and science. Chimps can’t do any of that, yet we share 99 percent DNA. Everything that we are, that distinguishes us from chimps, emerges from that one-percent difference. – Neil deGrasse Tyson

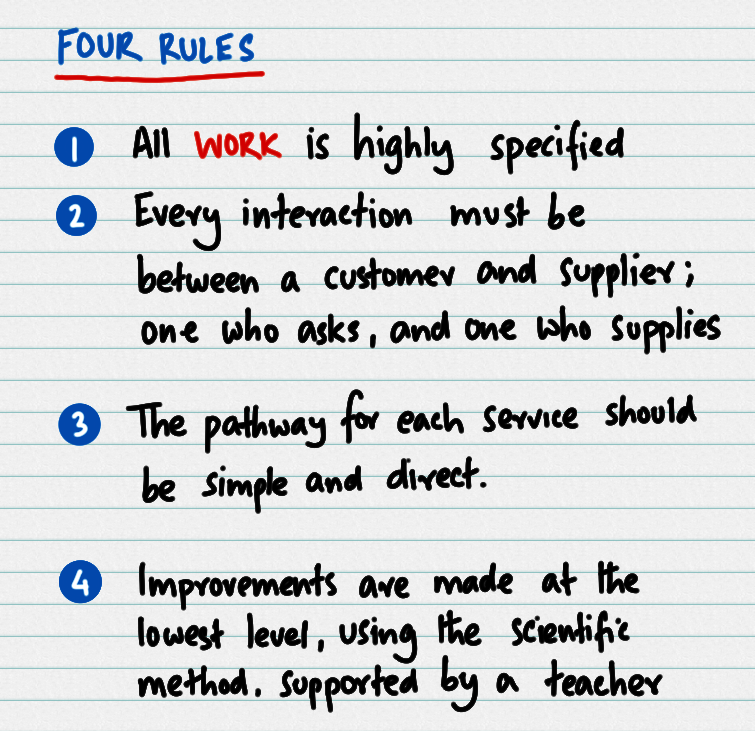

A 1999 paper by Steven Spear and H. Kent Bowen set out to decode the DNA of the Toyota production system – and seek out what made it work so well and at the same time so hard to imitate.

They argued that there were four principles, four rules, that grew over time that even the workers themselves could not articulate – they were just built into their way of working.

Let’s have a look at what they are and how we might use them as we continue to consider Lean Service design.

1. Specify work

Let’s start with what work and isn’t.

Certain things are not work.

I have a post about this somewhere and I can’t remember this exactly but I think the essence of it was that work is something you wouldn’t do if you weren’t compensated.

If you’d do it anyway, it’s not work.

Why would this definition be helpful?

Well, let’s limit it to the context of you’re a leader in a firm, someone who has a wide, creative role, who works with customers and develops services and enjoys the intellectual challenge of bringing something into the world.

You may be very well compensated for this.

But there is something that you don’t want to do. Something you need someone else to do. Something you are willing to pay someone else to do.

That’s work.

As you get closer and closer to the front line of where value meets the customer, figuring out what work is becomes easier and easier.

And this is when you must fully specify what the work is that you want someone to do.

What this means is systematically setting out, step by step. what needs to be done.

There are a number of approaches to do this, from Toyota’s own approaches to Crawford Slips, but they key is that there is a written specification of the work.

Now, when you ask for more resources and someone asks “for what work?”, you can provide your specification and say this is the work they need to do.

Most people will find this off putting, perhaps overwhelming, and file it in the too hard category.

2. Ask and you will get

The second principle is that every interaction is between a customer and supplier.

This is about a role, not about actual customers and suppliers.

In one case, your boss may be the customer and you the supplier.

In another instance, you may be the customer and the boss the supplier.

The point is that in each case, one person asks for something clear and unambiguous and the other provides something that is correct and complete.

This is about working on communication.

3. Follow the yellow brick road

The third principle is that of the path, each product or service should move along a simple or clear path.

First one thing happens, then the next and then the next.

Each action is a single piece of work that either does the work or puts it clean into flow so the next job can be done.

This is the service design work, working on getting each step working as well as possible.

4. Improvements done by the people doing the work

Train your teams and support them in making what they do better as they aim for continuous improvement.

All too often “improvements” are done elsewhere, in silos, and then imposed on people doing the work who then ignore it or find that it doesn’t do what they need it to do.

I have made this mistake and I need to learn when to recognize it – it’s hard to build something to make something easier for someone else.

You have to learn to see the world from their point of view and then start to work.

But if you’re the person doing the work you have an incentive to make it work better, more reliably, create less stress for you.

But you may not know how, so you need to pull support and guidance to get this done.

The takeaway

If you can’t do all this don’t be surprised.

The paper starts with noting that the approach is very hard to imitate.

It takes work to make the system work to do better work.

And Totyota has been working on this for decades.

One of the things you learn when you are exposed to critical thinking is that there are multiple ideas out there rather than one true idea.

Your job is to consider these ideas and weave together the ones that make sense to you.

Then you can apply what you’ve learned to your particular situation which is unique and different and requires careful thinking.

Or you can decide it’s all too hard and use some other form of management like command and control.

This approach was born in a factory and addresses products and services in that context of factory work.

There are other contexts like data work, or research work, or construction work, where you will need to develop approaches that are based on the principles and see how you do.

Now, I’m going to go and think about how to apply these principles in the work that I need to get done.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh