Monday, 6.36am

Sheffield, U.K.

There’s no map for you to follow and take your journey. You are Lewis and Clark. You are the mapmaker. – Phillipa Soo

In my last post we looked at waste and how the next step to improve things is to use mapping techniques.

Let’s just take a step back and look at what “mapping” involves.

A map is traditionally a diagrammatic representation of an area of land or sea showing physical features such as roads and cities.

When you go somewhere new, the first thing you have to do is look at a map – or these days pull up the maps application on your phone.

On a short trip earlier this year I used up all my roaming data and couldn’t access my maps app. That was terrifying. I had to ask people for directions! They, in turn, pulled out their maps apps and I took a photo so I could start to figure out where I was.

We are blind to the bigger picture without maps.

In physical spaces, then, we start with a blank space in front of us, because we don’t know where things are, and we reach for a map someone else has drawn so we can figure out where we are in relation to where we want to be and plot a route between the two.

This mapping metaphor does not translate cleanly from the physical world into the mental world.

The terrain of our mental worlds are not static and unchanging – they are constantly shifting and rearranging.

But we still use the term “mapping” when we try and understand a situation, so the first thing we have to do is reframe how we approach mapping – rather than it being something you reach for, it’s something you construct.

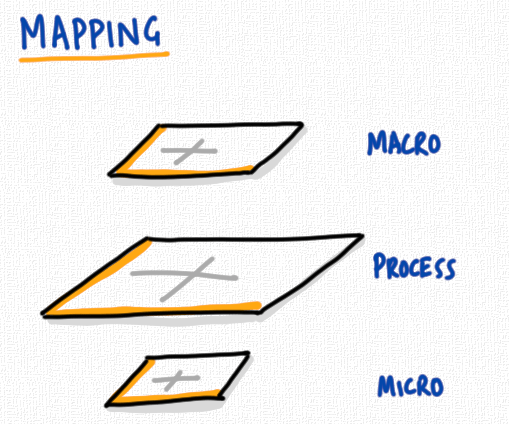

We have to learn to see the situation and map it at different levels.

The first level is the macro or systems level. This is where you look at the bigger picture and see how things fit together.

A technique for drawing a high level map is Rich Picturing from Peter Checkland’s Soft Systems Methodology.

There’s not enough space in this post to talk about Rich Pictures but have a look at this link and this one to get a sense of what’s required.

I created Rich Notes to help with this, but that’s also useful for mapping at the other levels.

At the macro level you’re looking at the landscape in front of you and identifying the mental equivalents of mountains and trees and streams and roads. The things that are in your way, the paths that already exist, the obstacles you need to ford.

Once you represent that situation on paper – in some kind of drawing that we call a map, you begin to see what sort of route you can take.

The most important thing with a journey is to see what the obstacles are and try to either avoid them or overcome them.

If you have a very high mountain in front of you, perhaps you need to find a way around it. If you have a river, can you build a bridge?

The obstacles you face lead you to decide the things you need to do – and now you can come down to the next level of mapping, which has to do with process.

In process mapping you look at the steps to follow.

As someone once said, “Life is one damn thing after another”.

A process map is about getting those damn things down on paper.

Start to finish, beginning to end, break down what is happening step by step.

A common technique is brown paper mapping, where you tape a long strip of brown paper to the wall and use post its and markers to step through the process.

These days it’s probably easier to use a spreadsheet or online tool.

Process mapping helps you see what is being done, or map out what should be done – and as you do this you’ll see areas of waste, where there is repetition or rework or delay.

And once you see waste, you can start to think about ways to remove that waste.

The bottom level of mapping is the micro level – which looks at the details of what needs to be done.

If you think of the macro level as the way things fit together and the reasoning behind what we’re doing, and the process level as the plan that we should follow, then the micro level is executing the plan, where action takes place.

And we need to lay that out, list the steps that need to be done and create tools to help us, like standard operating procedures, instructions, checklists and tests.

It does take some time to learn and practice mapping techniques at these levels, but one thing you should think about is who is doing the mapping.

Are you going to do it with your business – take hold of the pen and talk to people and map what they tell you?

This is what I do a lot of the time.

But you can also give them the pen and ask them to work through the situation in a group.

That gives your team the opportunity to get involved and think through what they do and what the bottlenecks and issues are with the process.

The thing to remember is that at the micro level your teams are often asked to follow the approaches imposed by management, whether they improve the customer experience or not.

If you are a manager you have the power to change the system – your workers don’t – and so once you see what the issues are it’s up to you to figure out how to make things better.

Hard work is not the answer, better systems are.

I came across a pointer to Miriam Suzanne’s post We don’t need a boss, we need a process, and that’s sort of the thing I’m going for here.

Think of mapping as a way of getting down what’s in your mind on paper – it’s just a representation, not reality.

It’s a tool to help you get what’s in your head and other people’s heads down on the page so that you can empty your mind and have the brainspace to focus on what to do next.

And that’s the point of a map, to help you on your way.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh