Tuesday, 9.18pm

Sheffield, U.K.

Are you stalking me? Because that would be super. – Ryan Reynolds

Too many of my posts recently have been about generative AI.

I’m sorry, this is one more. It’s an important topic after all.

In my last post, I wrote about the future for human work, in particular about writing and knowledge.

My blog is not particularly widely read. I don’t actively promote it. It’s a place where I work on ideas by working on sentences. If someone reads a post and finds it useful that’s a bonus.

So, after I wrote my AI post, I thought, why not ask ChatGPT to write an article in my style?

Here’s what it started off with.

“Karthik Suresh’s writing style is characterized by a lucid, engaging tone that often mixes personal insights with a deep understanding of technology, business, and strategy. His pieces frequently strike a balance between being informative and approachable, with a hint of philosophical reflection.”

My first thought was, “Ok, well that’s nice”.

Followed by, “Sh*t, ChatGPT knows my work”.

Now how should I respond?

Let’s review the basic options. Fear. Flight. Fight. Food.

Actually, let’s go with the motivational triad: pain; pleasure; and sex.

The last one is not an option, so let’s consider the routes to pain or pleasure.

GenAI is going to take jobs. There is no doubt about that.

Transcribers. Translators. Voiceover artists. Visual creators. Writers.

A whole lot of jobs are going to change forever. That’s pain right there.

But is there pleasure?

I think that if you learn how to use these tools it will make you better at what you do.

I’ve worked on a couple of technical papers that I believe are stronger because I used these AI tools to help me learn quickly about concepts that are quite tricky.

I asked a person for help, one time, and was told I should join their class and it would take three months to learn.

Or….

I could get an AI to help me write some code, explain how things worked and figure it out from there.

I chose the easier option.

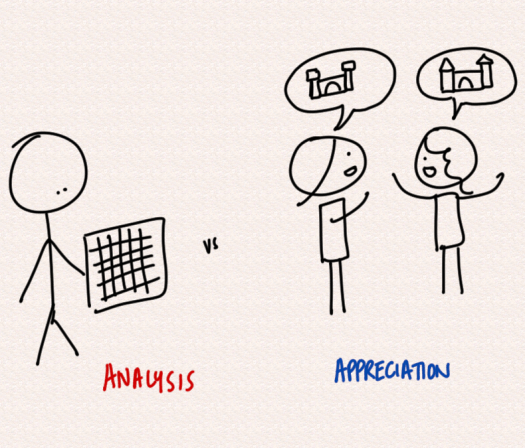

I asked ChatGPT to tell me how I could make my writing better.

It told me that my work lacked boldness. It wasn’t provocative. I’m too moderate in my views. And I don’t provide enough detail.

That’s good feedback. Points to consider and work on.

That’s pleasurable.

Here’s the thing. Options can be both good and bad at the same time.

The way you react to your options delivers good or bad results.

Me… the technology isn’t going away.

If a robot has peeked through the window and read everything I’ve written and knows more about how I write than I do myself – what should I do?

Throw stones at it and drive it away?

Or make friends with it?

What would you do?

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh