Friday, 9.10pm

Sheffield, U.K.

The first writing of the human being was drawing, not writing. – Marjane Satrapi

What is the point of a blog?

I started thinking of it as a place to showcase my work – to display what I knew , to prove to others that I did know something.

I learned, as I wrote, that I had more to learn, and what I knew I began to question.

I wrote in paragraphs, then in sentences, and later in paragraphs again.

I wrote ponderous prose, then simple words, then elaborate constructions once again.

I whined about writing in some posts, and crafted reasonably complete essays in others.

I imagined that what I wrote would be the way the world saw me. I later realised that everyone is busy and no one is looking.

I learned that your blog is a place where you can work on what interests you. It’s a place to learn. It’s a place to practice. It’s like working in the middle of the hustle and bustle of the biggest coffee shop on Earth. You’re surrounded by people, but you can also be alone and focus on your work.

And I do need to get on with work.

I have to produce a thesis in a couple of years, and there is lots of reading and thinking I need to do.

John McPhee writes about the difficulty of getting started with writing. Say you need to write about a bear. You start by writing to your mother. First, you write about how hard it is to write. You complain about the topic. You ask why you chose bears in the first place. You mention the bear has a 30 inch neck and could keep pace with a horse. And then you delete all the whining and leave the bit about the bear.

If you are reading these words, or the next few hundred thousand, I apologize now. They will follow McPhee’s advice, although with the unnecessary stuff left in until I get around to the edit.

I need to work out ideas, and the way to work out ideas is to talk about those ideas and to think about what other people have said. This blog is my place to work out those ideas. And sometimes, those ideas will be half done and I will run out of time and have to stop.

So where am I right now in the production of this thesis?

The topic I’m working on seems laughably general and terribly important at the same time.

I’m interested in how to make better choices. It’s one thing doing that as an individual, and a whole other thing doing it as a group. The research question that I’ve backed into is how to work better in groups.

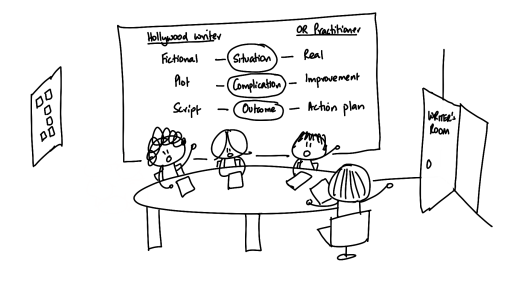

A rabbit hole that I’ve gone down recently is the phenomenon of a “writer’s room”. This is a thing in Hollywood. And it’s something that I need to understand.

The writer’s room is a workplace tradition that creates a space in which a group of writers collectively author television scripts (Henderson, 2011).

Okay, so I’m out of time. One of the things about this phase of the blog is that when I need to stop, I will, and carry on another day.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh

References

Henderson, F.D., 2011. The Culture Behind Closed Doors: Issues of Gender and Race in the Writers’ Room. Cinema Journal 50, 145–152.