Sunday, 7pm

Sheffield, U.K.

The only reason for time is so that everything doesn’t happen at once. – Albert Einstein

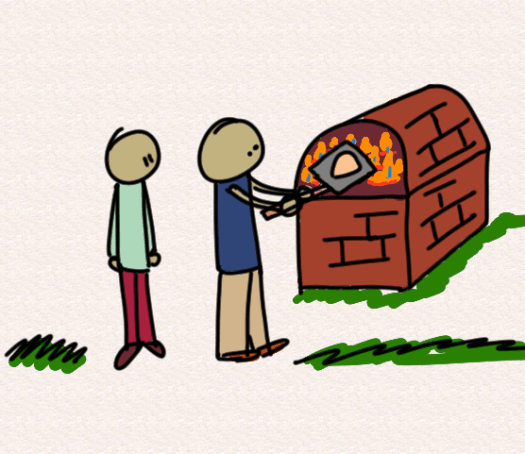

We watched “Race across the world” recently and one of the scenes that stuck with me is where a participant helps a farmer get their oven ready and bake some bread – and is overwhelmed by the simplicity and purity of that life.

It might also be rather boring if you had to do it day in and day out.

A documentary on the increasing use of anti-anxiety medication remarks on how we spend more and more of our lives in our heads.

Well, in a sense, that’s all we do – everything we experience is really constructed our brains.

But more generally, our lives are not so much lived as spent watching screens.

We spend around 7 hours a day on screens – both for work and for entertainment.

The difficulty is that settling down and enjoying something on a screen – a game, a movie, a series – is almost always the easiest thing to do.

And therefore it’s perhaps the preferred thing to do.

It’s windy and cold out. Do you want to go for a walk? Or would you rather just watch something?

It’s always easier to do the easy thing.

That’s why water heads downhill.

This experience from our personal lives also happens in social and work situations.

It’s easier to go along with bad processes than to try and change them.

Sometimes things are the way they are because it was easier to do them this way than a different one – if things are hard to do you’ll find that people will just stop doing them.

Take commuting to work, for example.

It’s bad for you – we typically put on a couple of pounds – or a kilo or so a year for every year of a job with a long commute.

Staying at home isn’t perfect either.

Some of the mental health impacts include “less motivation, body image, depressing/negative content, vicarious living, mood swings, no social interaction, reclusiveness, dependency on screens, habitual use, arguing online, jealousy of others, feeling unproductive, guilt, toxic people online, socially anxious, hard to switch off, irritable, distracting, losing attention span.”

Trying to make all these variables work is a little like baking bread.

It’s actually quite simple to make bread – flour and water, knead for a while until it feels right, and give it some heat.

But of course, the kind of flour matters. Salt might help. Yeast makes a difference. The amount of time you spend stretching and kneading affects the quality of the loaf.

Knowing what I now know I think trying to figure out what to do with your time has to start with the basics.

Try and make a recipe that does three things.

First, optimise for health: get your food right and build movement into your day.

Second, optimise for relationships: make time for people because it’s easy to slip into a world of your own.

Third, optimise for peace of mind. You’ll know when you have that.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh