Monday, 8.43pm

Sheffield, U.K.

It’s the steady, quiet, plodding ones who win in the lifelong race. – Robert W. Service

There’s an image that pops up every once in a while along with a story – it’s a WWII plane riddled with holes and the engineers look at it and say, “We need to armour plate where the holes are.”

Then someone says, “No, we need to armour the places where there are no holes – those are the hits that brought the planes down”.

In other words, we have to learn that often the thing to fix is the thing we don’t see.

This particular decision point comes up quite often in life.

In investment, we see people making quick money through active trading. We see their stories and their triumphs.

We don’t see two things.

We don’t see the failures – because people don’t like advertising that.

And we don’t see the millionaires who got there by putting their money in an index tracker and letting it simply compound over time.

I tell my kids that I can guarantee they will be millionaires.

It’s simple maths.

Your savings will double around every 12 years on average.

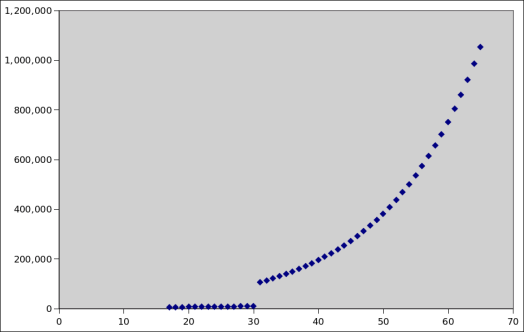

Say from the age of 17 you do enough to put away £300 times your age every year.

So at 17, save up your pocket money and do odd jobs and stash £5,100 in the market.

Do that every year, and at age 30 you put in £9,000.

You will have saved nearly 100k over that period.

Now, sit back and relax.

On average, you should see growth of around 7% a year if you invest in an index tracker and the global economy grows.

Some years it will be less, some years more.

But in the long term it will work out.

You don’t need to put in any more money.

By age 65, you will have over £1 million in your account.

Take a look at the chart.

Investing is really as simple as that. To do well, start early, save as much as you can, invest it in a tracker, forget about the market and enjoy your life.

Good investing should be like watching paint dry.

The payback will come years later.

Now, precisely how much would you like to pay me for that advice?

Probably nothing – even though it is the most valuable thing you could possibly learn from me.

But, what would you pay for some day trading training, perhaps forex on margin, or perhaps how to buy and flip houses, or how to rake in views on YouTube – all these get rich quick schemes that are designed only to do one thing.

Benefit the person selling you the stuff.

Now, what do you do when someone comes trying to pitch you something.

The correct answer is, in almost every case, “No thanks.”

Which makes it hard to be a salesperson.

If you ask people what they think about this thing you have the chances are that they’ll be polite and say it’s nice.

What you’ve got to listen to is what they don’t say.

What are the risks for them – how could they lose out?

If this thing is really valuable, if it’s something that could help them then you should try and get that across.

But you’ve got to recognise that there is an entire industry that’s also putting messages out there that aren’t good for them, and people, once bitten, turn shy.

I think business may be splitting into two very large factions.

On the one hand, you have companies that totally dominate their ecosystems, like Google and Microsoft and Apple.

I don’t know if you’ve ever tried to browse the Internet on a web browser that only supports html but it’s pretty much impossible.

Google and javascript has simply taken over the world of the web.

Wikipedia works, fortunately.

So you’re locked into those ecosystems with no choice at all.

On the other hand, you have hugely creative options for people that want to have some choices.

I bought my laptop from Framework and it has replaceable parts and can be upgraded.

I bought a Devterm from Clockwork Pi, again a machine that can be modified and extended and is just simply fun to use.

But if you go out and look for advice you’ll only see what the companies want you to see – the vast echo chamber makes it looks like you have no options but the obvious options, and there is no one to tell you to consider a different option.

Even I hesitate – should I talk about my experiences with Free software and Open hardware?

Is that useful or not?

Time will tell.

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh