Monday, 8.24pm

Sheffield, U.K.

Your only obligation in any lifetime is to be true to yourself. Being true to anyone else or anything else is not only impossible, but the mark of a fake messiah. – Richard Bach

There is, or rather was, a small tree in our garden, or a large bush, depending on how you see things.

It was of questionable utility, good for hanging toys on, bad for squeezing past and brilliant at pulling jumpers and ruining clothes.

Still it was there, and we didn’t want to get rid of it. Instead, we trimmed it back and tried to live with it.

This summer it leaned over, further and further, stretching out towards the sun until the other day I tried, just to see what would happen, to push it back.

And it moved.

Not just a little bit, but completely loose in the soil. So wobbly in fact that it didn’t seem to make sense to leave it there.

So I pulled it out – not with any great effort. It was so loosely rooted, possibly rotted, that it came out with no difficulty at all.

Certainly without the kind of difficulty one would expect from any self-respecting tree with proper roots.

I am no gardener and this may seem like a not very nice thing to do but in my defence, the tree had it coming.

And I suppose that points to two things that are worth remembering.

The first is that some problems may appear so big when you look at the branches that you don’t realise that they have no roots – and you could simply pull them out if you were minded to.

The other is that if you want to build anything of lasting value you need to look at what really matters.

It’s a metaphor that seems quite applicable to our modern lives.

You can spend a lot of time taking pictures, posting them on social media, harvesting likes and comments and not have any time left over to put together an album at home.

If you create content for platforms – putting all your stuff on Medium or LinkedIn – what happens to your own site?

That’s why so much advice tells you to create your own portfolio – put the time aside to create your body of work.

Perhaps you can do both – create a deep store of original content and be very good at promoting it to the world through channels – be the kind of person that can tend root and branch equally well.

Or you can eschew the fluff and focus on the work.

I suppose we all feel that it would be nice to be rich and famous.

But really, how happy would you be once you had all that?

It’s possible that might depend on how deep your roots were – whether you knew how to cope with sudden wealth or not.

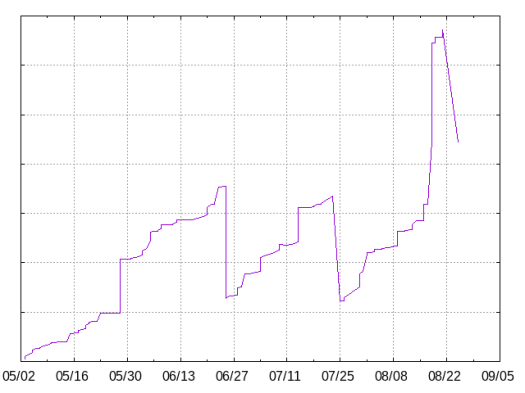

Most lottery winners, we are told, get through all their winnings rather quickly.

Few invest it in a diversified set of index trackers.

Maybe we should remember a Zen koan – one of those little stories designed to open one’s mind.

A monk asked Jōshū in all earnestness, “What is the meaning of the patriarch’s coming from the West?”

Jōshū said, “The oak tree in the garden.”

Cheers,

Karthik Suresh